Like many direct-market vegetable farmers, Matthew Kurek had no farming experience when he started farming. Thanks to a combination of hard work, great markets, and a bit of luck, he is now one of the success stories. His farm, Golden Earthworm Organic Farm in Jamesport, New York, has a CSA with 1,350 members, a farm stand, three farmers markets, and restaurant accounts. The farm supports two full-time farmers and provides seasonal jobs to more than 15 employees.

Rewind to the early 1990s. Matt, a culinary school graduate in his early 20s, was working in restaurants in New York City. He loved vegetables and natural foods, and he found himself spending more and more time at the city’s farmers markets. In 1994, giving in to the siren song of farming, he quit his cooking job and planted about 1 acre of vegetables, which he sold to restaurants, small stores and one farmers market. “I started really small,” he said, “no business plan, no equipment, no knowledge. There was a lot of trial and error!” In 1997, he had the opportunity to lease his current farm on Long Island. Because the land was protected by a conservation easement that permanently preserves it for farmland, he was able to lease it for just a few hundred dollars per acre per year. So Matt scaled up to 10 acres and added a few more farmers markets. He also started a small CSA on Long Island.

The watershed year for the farm was 2002. That year, a non-profit organization called Just Food approached Matt about growing for a CSA in Queens, in New York City. Just Food had become active in trying to connect urban residents in the five boroughs of New York City, many of them low-income people, with fresh food. Many farms in the New York environs got a start with CSA in those years. Just Food’s role is to make the link between a CSA group and the farm. They advise the CSA core group and the farm about how best to work together and they offer any necessary support. The CSA core members are responsible for organizing everything else - money, staffing, site, etc. All the farmers have to do is deliver the produce. “Our CSA program began on a trial basis with just a few members. Everything went well and the CSA expanded each year by word of mouth and some lucky media exposure,” Matt said. “In 2002 we started our first Just Food-coordinated CSA group in Forest Hills, Queens. There were about 50 members in the group at the time. In 2003, the Douglaston group started. In 2006 Jackson Heights. 2007, Astoria, Flushing, and Sunnyside.” “We are forever indebted to the wonderful work and the wonderful people at Just Food,” Matt said. “They are responsible for our six large groups in Queens. Our other 16 groups on Long Island are arranged and managed by us.”

The Just Food groups are diverse - both culturally and economically. One group is predominantly Chinese, so Golden Earthworm buys some Chinese specialties from another farmer to supplement their shares. “Every group is completely different,” said Maggie Wood, Matt’s wife and the marketing manager for the farm. When working with the Just Food groups, the farm sets the share price and leaves it up to the organization to add an administrative fee if it wishes, collect the money, and pay the farmers. Golden Earthworm offers a free share for every 30 paid shares. “Some groups have 10 to 15 low-income shares,” Maggie said. “We’re at the point where we can forgive a lot on our end.”

Golden Earthworm Organic Farm also participates in a United Way program to supply fresh food to food pantries. The farm delivers to a central location, and the food pantries pick it up there and take it back to their own distribution centers. United Way pays an agreed upon price each week for 22 weeks for the produce. All of the Long Island sites are pre- packed individual boxes which are picked up at self serve locations. “We found it’s a lot faster and safer,” Matt said. “We were always worried that people at the end would get left out, and we didn’t want someone (an employee) to have to sit in the barn all day to monitor the distribution. Now we just tell members they can come between 11 a.m. And 8 p.m. and get their box from the cooler.”

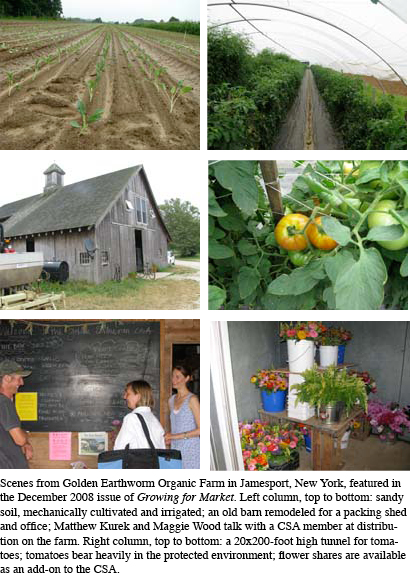

The CSA also offers fruit shares from a nearby farm and flower shares as separate add-ons to the vegetable share. Golden Earthworm is certified organic, though Matt isn’t sure it’s needed for the CSA. “We continue to be certified organic because it saves a lot of extra effort, not having to answer questions about our growing practices. We would be farming the same way regardless of the standards, but it is not always easy conveying this to people, so being certified organic is a simple way to communicate our practices to the public. It is also important if we need to sell any surplus to stores or restaurants,” he said.

Expansion of this CSA activity all happened concurrently with expanding production. Matthew was able to lease a second parcel of protected land, bringing his planted acres to about 65. He restored an old dairy barn on the property into a combination of packing shed, office space, and CSA distribution space. He met and married Maggie Wood, an architectural designer who specializes in sustainable building and green homes. Maggie took over marketing, including developing a beautiful web site. Matt and Maggie, who had been commuting to the farm from about 25 miles away, were able to buy and move into a house next door. In 2004, he was joined in managing the farm by James Russo and the next year the two farmers made their partnership official.

James, a native of Hadley, Massachusetts, attended Stockbridge ag school and graduated with a degree in soil science from the University of Mass at Amherst. Prior to joining Matt at the Golden Earthworm, James had worked on a few smaller farms and had been field manager at a large north fork vineyard. Matt and James applied for the H-2A program and started bringing as many as 14 workers, nearly all related to one another, from Mexico every summer.

Something is always being harvested at their farm. On Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, they pick for the CSAs. On Thursdays and Fridays, they pick for two farmers markets on Saturdays and one on Sundays. They also have a farmstand at the end of their driveway all day on Saturdays. Although Matt started with the idea of growing for restaurants, that has become an increasingly small portion of their sales over the years. “Things have shifted in just the past two years,” he said. “Now chefs are coming to the farm stand and saying ‘we’ll pay you whatever you want’ because they want to have local food on the menu.” Vegetable production Golden Earthworm Organic Farm is about 60 miles east of New York City, just east of where Long Island divides into two forks. The south fork, which faces the Atlantic Ocean, is a summer playground for wealthy city people. The north fork held on to its agricultural heritage for a long time, especially with potato and vegetable production. In the past few decades, though, much of the farmland has been converted to vineyards for a flourishing Long Island wine industry, and to ornamental nursery production. Land on the north fork that is protected from development sells for $50,000 to $60,000 an acre or more; developable land is much higher. The best hope for a new vegetable farmer is to do as Matt did, and lease ground that is protected by a conservation easement. (See the November 2008 issue of Growing for Market.) “Ninety percent of the land we farm is preserved and probably would not be available to us if it had not been preserved,” Matt said. “It is very difficult for first-generation farmers to buy their own land.”

But even with the land tenure issue resolved, growing vegetables isn’t always easy on Long Island. The temperate climate allows for a long season, but strong winds, especially in spring, stunt plant growth, Matt said. This year, Golden Earthworm Organic Farm put up its first high tunnel, a 20x200 foot Haygrove Solo model. They laid landscape fabric end to end, and planted 500 tomato plants. By late July, the tomatoes were bearing heavily. “Our first experience growing high tunnel tomatoes was generally very successful,” Matt said. “While it took extra time to manage the high tunnel compared to growing tomatoes outdoors, the quality and quantity of the tomatoes - combined with cost savings of little spraying - more than offset the extra management. We tested three different determinate red tomatoes, one cherry tomato, and one heirloom. The determinate varieties did very well and grew about 2-3 feet taller than they do outside and needed stronger stakes than we expected. The cherries grew way too tall and, without doing some other kind of trellising so they can be lowered throughout the season, are kind of unmanageable in a high tunnel. “We began to neglect the high tunnel late in August and didn’t attend to a growing whitefly and worm problem so a small portion of the tomatoes were affected by these insects. It is very important to vent the tunnels correctly. All in all, we were very happy growing in the high tunnel. I don’t have any compiled yield info right now. “There some great advantages to our location but the wind is an enemy here! It is pretty temperate and if we can take the wind out of the equation (by growing in a high tunnel) it makes a big difference. Since we have good farmers markets it is very helpful to have certain crops (like tomatoes) earlier and later in the season than other vendors. The quality is also improved-- something that our customers like!”

Deer are also a big problem for vegetable farmers on Long Island, and all of the production land is fenced. Quality of life Matt feels that it took him a long time - 14 years - to make a success of his farm. But now he has achieved his dream and reached a scale and lifestyle that suits him. And he’s only 38 years old. “Our CSA program has allowed our farm to be profitable and provide a comfortable living wage, even for here on Long Island, for James and myself. We are very happy that we can say this - after many long years of building up the business. Although there are many variables and challenges, market farming can be satisfying and economically viable. Currently, it seems to be a particularly good time for local/regional producers, thanks to a large amount of societal interest. “There are several things that I think are important to starting and succeeding in creating a sustaining farm business: reasonably long term commitment, patience, ability to learn quickly, access to the appropriate amount of money for the farm’s scope, ability to adapt to changing circumstances, at least a couple of years of hard farm work, a good farm support network, and a good, realistic plan (even if it is just a starting point).” a For more information, visit http://www.goldenearthworm.com