At a time of life when most Americans are thinking about retiring from work, many people are continuing to farm or jumping into it with all the enthusiasm of youth. Retirement farmers throughout the U.S. are proving that even labor-intensive vegetable and flower farming is not necessarily a job for the young. Older farmers are making significant contributions to their communities, while reaping enormous benefits themselves.

Retirement-age farmers come from two pools: those who keep farming past the traditional retirement age; and those who start farming when they retire from previous careers in their 50s or 60s.

Farmers are well-known for working much later in life than other workers. More than one-fourth of all active farm operators are age 65 or older, compared with only 13% of the overall labor force. In fact, the average age of farmers in 2002 was 55.3 years, according to USDA statistics, and it has been climbing steadily since 1978. The proportion of farmers age 55 and over has risen from 37% in 1954 to 61% in 1997.

Among organic farmers, the average age is slightly younger - about 51 years old, according to the Organic Farming Research Foundation’s 2001 survey. Sixteen percent of the respondents in that survey were over 60 - up from 12% in 1993. An Illinois study in 2000 also found that farmers are twice as likely as other workers to keep working beyond age 65.

The reasons for the delayed retirements are not quantified by statistics, but among the possible explanations is the fact that farming is so much more enjoyable than many other kinds of work. In addition, on the farm there is no pressure from an employer to reduce payroll, and younger workers are not around to remind older farmers of their age. A need to keep making money is certainly another reason for many farmers, although statistics show that most farm families save more for retirement than the general population. (More on page 7.)

The second pool of older farmers is people who have left other jobs and started farming later in life, or expanded a part-time farm into a full-time endeavor. The number of people in this category is hard to quantify because it isn’t tracked by the Ag Census. Anecdotal evidence, though, suggests that many people get into farming as a retirement job.

In all, 290,900 people in the 1997 Ag Census identified themselves as “retirement farmers.”

Financial benefits

Money is one reason to choose farming as a retirement job, even though no one makes a lot of money farming, especially when just getting started. For some people nearing retirement, a small income from the farm can be the stopgap to get them through the years until their Social Security income becomes available or to sustain them a few years longer before taking Social Security, which will increase the monthly payment for the rest of their lives.

Carolyn and Quinton Tschetter of Oskaloosa, Iowa, say that their flower farming business “is our ticket to paying for sky-high health insurance rates, at least until Medicare.” Both are in their early 60s, and Carolyn retired last year from her career as an elementary school teacher. Quinton also runs an antique store and home renovations business.

The Tschetters’ farming business has grown dramatically in anticipation of “retirement.” They have 5 acres of cut flower production, which they sell at the Des Moines Downtown Farmers’ Market, the Pella Farmers’ Market, to florists in five towns, and on the farm. They have four 26x96 hoophouses and one shade house.

For many retirement farmers, though, earned income is probably not as important as the tax benefits of farming. The federal tax code and local governments offer significant savings to people who are really farming their land.

On the local level, property taxes are sharply lower for farmland than for residential land. Bill Gillen, a 67-year-old farmer in Amherst, Massachusetts, owns 10 acres in town where he grows produce and sells it at the farmers’ market. “I have land that’s probably worth $2 million,” he said. “But we intend to continue to farm it.”

Les and Debbie Guile have a beautiful small farm in the mountains of northwestern New Jersey, an area that is under intense development pressure. Their farm is protected from high property taxes by the state’s Farmland Assessment Act.

The key to winning an agricultural exemption for land is to actively farm it. Earlier this year, actor Mel Gibson applied to have 17 acres of his 75-acre Greenwich, Connecticut, estate classified as farmland. Under the state law, farmland is appraised at $2,000 per acre. Gibson’s land is appraised at $170,000 per acre. With an agricultural exemption, he would have saved $10,000 on his $137,000 property tax bill for the estate that is valued at $17.7 million. In addition to the 28-room mansion, pool, tennis courts and two guest houses, Gibson has a barn where he keeps sheep, donkeys and chickens. But Greenwich officials rejected his request, saying “Anyone can have a few pigs in their back yard, but a viable farm is more than having something for personal use. It’s about producing a viable product.”

Most states and local governments require proof that the land is being farmed as a profit-making business. The Guiles get a form from the state of New Jersey every year requiring them to certify that the land is still being farmed. They have to provide the Schedule F from their federal income tax return, which proves they have farm income.

Tax deductions

The income tax code also provides many benefits to farmers. When a hobby such as gardening becomes a profit-making business, all the accouterments of that passion become tax-deductible, including tools, tractors, equipment, greenhouses, barns, plants, etc.

Jack Kroeck moved to rural Arkansas when he retired at age 57, and started a large garden to feed his family. He soon realized he was growing more than they could eat, so he started selling at farmers’ markets, and over the next few years his sales doubled each year. Once his hobby became a profitable business, he was able to deduct all his expenses.

“I always looked upon my market sales not as an income generator, but as a way to pay for my garden expenses,” he said. “With that outlook I was able to have freedom ordering seeds, could add to my tool assortment and cover the cost of an irrigation system. In short, the garden paid for itself in addition to feeding the family.”

Ross Faris of Your Neighbor’s Garden in Indianapolis, Indiana, says “the profit generated is enough to make a significant increase in my total income; I still haven't gotten to the point I think I could make it without my retirement check. There have been tax advantages including being able to deduct 80% of the expense of two SUVs I use to move produce to farmers' markets. Also, being able to continue to invest in my IRA is definitely an advantage.”

He explains that he and his wife Sherry own a small, fuel-efficient car that they use for personal reasons but they don’t need to buy a second car because of the SUVs that are owned by the farming business. According to IRS rules, a vehicle can be deducted as a business expense if it is used primarily for business purposes; the IRS allows some personal use, provided you keep track of personal miles, multiply it by the standard mileage allowance, and deduct that amount from the business expenses.

Ross added: “I also own a farm in Northern Indiana where I grow some sweet corn, rent ground out for row crops and rent the farm house out as a retreat ( I call it my bed and breakfast where you make your own bed and make your own breakfast.) The income off the rent of the land and the house is part of my gross income; I then deduct all farm expenses including depreciation, insurance, maintenance and taxes. The farm is my mom's birthplace and I bought it originally as a sentimental investment then decided to try to earn some income from it since we don't get to visit very often (it is 125 miles one way). The farm is usually unprofitable and Your Neighbor's Garden is usually profitable; netting them usually gives me a small taxable income. So in addition to the profit from Your Neighbor's Garden, I receive some additional tax benefits.”

Social and emotional benefits

Whatever the financial implications of retirement farming might be, they are clearly outweighed by the non tangible benefits farming offers. Every person we interviewed for this article expressed joy and satisfaction at their farming life.

“I'm having so much fun,” wrote Joan Jendro, who started growing flowers in northwestern Wisconsin last year at age 62. “It is a blessing to have the space, the time, and the good health to engage in flower farming. Every moment I'm out there, even when I'm murdering weeds, is heavenly.”

Jack Kroeck wrote: “Besides the economic benefits of paying for the garden, the market provides a soul-fulfilling role in my life. I have met folks at market who are now friends, have learned from other market growers, and always enjoy the interaction with the market customers. I truly believe that farmers’ markets are part of the glue that binds communities together in this day and age. It's a slow-down place that lets folks smile and take bigger breaths. It gives both customers and sellers stories to tell others about their experiences at the market, adding depth and meaning to our lives.”

Bill Gillen, 68, said: “Accounting in our culture is a real problem because we don’t know how to account for our real bottom line.” For him, that real bottom line includes his stature in the community for keeping his Amherst city land open and farmed; the joy of having his 9-year-old grandson working at the market with him on Saturday mornings; the social interactions at farmers’ market. He also values the tradition he and his wife have developed around harvesting on Friday night. Customers and friends show up at 5 p.m. and help harvest till 8:30 or 9 p.m., then take food from the garden up to the house and cook a big dinner.

“There are all these kinds of social benefits,” he says.

Richard Rudolph, in Standish, Maine, also finds immense satisfaction in farming. “It provides a definition for who I am,” he said.

A college professor for 32 years, and a dean at the time of his retirement from the University of Massachusetts at Boston, he was attracted to the practical work of farming. “I had a real need to do something with my hands as well as my head,” he said. “There is something very concrete and specific about farming. Compared to teaching - where you never really know who you’ve reached, I know that I got three bushels of green beans.”

Richard retired in 1996, taught part-time for a few years and has been farming full-time since 1998. Now 64 years old, he sells at four farmers’ markets and to natural foods stores and he gives away food to pantries in Portland, Maine. A longtime activist for sustainability and the environment, he viewed farming as an extension of his political beliefs.

“Farming is a huge commitment to the environment, and to the larger society,” he said. “How are we ever going to turn this (corporate agribusiness and its associated health and environmental problems) around unless we get back to the land? Someone needs to be doing this work and I figured ‘Why not me?’ A lot of people will commiserate about what’s wrong with this and that; for me, I felt I needed to try to be part of the solution. Organic agriculture and locally grown food are part of the solution.”

Physical considerations

Market gardening is without a doubt hard on the body at any age, but the retirement farmers we interviewed weren’t discouraged by the physical demands.

“I firmly believe that working outside in the fresh air, feeling well-prepared soil, smelling the fresh scent of flowers or fresh cut hay, and harvesting the rewards of all your labor, will keep you healthy. We may not be able to move as fast or bend as easy as we did when we were younger, but I think all the daily activity helps keep us in shape and from having to pay for a membership in some health club or gym,” said Ed Phillips of Piedmont, South Carolina, who decided to retire from his landscaping business last year when his two children graduated from college.

“The physical side presented its own challenges,” said Jack Kroeck. “I teach yoga and am physically fit...or at least considered myself so. This physical labor led to a knee problem and back aches that I tended to through yoga.”

Julia Maul, who sells plants and cut flowers at the farmers’ market in Lawrence, Kansas, says her biggest challenge has been performing the manual labor required.

“My approach is to evaluate all tasks from an ergonomic viewpoint with emphasis on work simplification, energy conservation and proper body mechanics. Knee pain from a torn ligament that had to be surgically repaired three years ago is a daily reminder to me to follow my own rules,” said Julia, who is 58 years old. "My hope is to remain involved with horticulture for many years to come. As my body ages, I hope to be able to continue to evaluate and adapt tasks so I can continue to enjoy my passion!"

The key to getting all the hard physical work done as bodies age is to have young, strong people around to help. Julia Maul says she keeps a list of tasks she can’t do and when her sons stop by, they help her. Richard Rudolph has three interns and three employees. Bill Gillen has an employee who also helps Bill maintain several commercial properties he owns.

Older farmers also try to reduce the physical stresses with equipment and tools. Mechanical transplanters replace hand planting; plastic mulch replaces hand weeding; motorized vehicles replace garden carts for hauling loads to and from the field. Retirement farmers have to be a lot more aware of how they are using their bodies.

“I do realize the farm is only an injury away from not being a farm,” Bill Gillen said.

Achieving balance

Having retirement income also allows older farmers to not be as obsessed with farming as some younger farmers who need to earn all their income from the farm. All the people we interviewed talked about taking time away from the farm to visit children and grandchildren, to pursue other hobbies and to be involved in their communities.

“I think the real danger is not knowing when to say enough is enough,” said Richard Rudolph, who says he plan to farm at least until the age of 70.

And why not? These farmers are enjoying themselves, keeping fit and healthy, doing work that is important, and remaining a vital part of their families and communities. Surely that’s got to be a good way to grow old.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

.png)

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

Here's a system to track all those details

Here's a system to track all those details

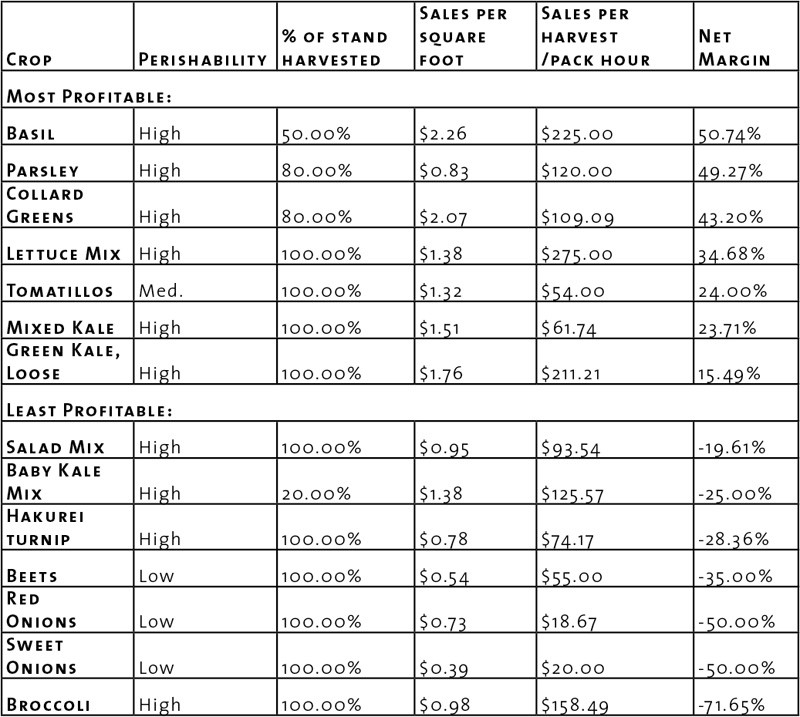

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).