This article originally appeared in the March 2011 issue of Growing for Market, the magazine for market farmers. Please join us; GFM is available by mail or online. Click here for subscription options.

This promises to be the year that tomato grafting reaches the mainstream, with the options for rootstocks increasing and some companies selling grafted plants. Grafting vegetables is nothing new — it’s been practiced in Asia since the 1920s — but it’s still relatively uncommon in the United States. Growing for Market published an article about grafting in 2008, and we have been watching interest grow quickly. But there still are many growers who question its value, given the fact that seeds for the tomato rootstock cost as much as 44 cents each.

So we decided to look into the economics of grafting tomatoes to help growers determine when the expense and labor are worth the results. We turned to Cary Rivard, a new vegetable Extension specialist at Kansas State University. Dr. Rivard’s graduate work at North Carolina State University focused on tomato grafting. He has been presenting workshops about grafting this winter, and his presentation is the basis of this article. We also talked to Andrew Mefferd, who is responsible for the tomato trials at Johnny’s Selected Seeds research farm in Maine.

The basics

Grafting involves growing two sets of plants: the variety you want for its fruit, called the scion variety, and a special rootstock variety with extra vigor and disease resistance. When both sets of plants have reached a similar size, with about two sets of leaves, you cut the stem of both, and attach the scion plants to the rootstock plants with a silicon clip that holds them together. The two stems grow together, the cut heals over, and you have a grafted plant.

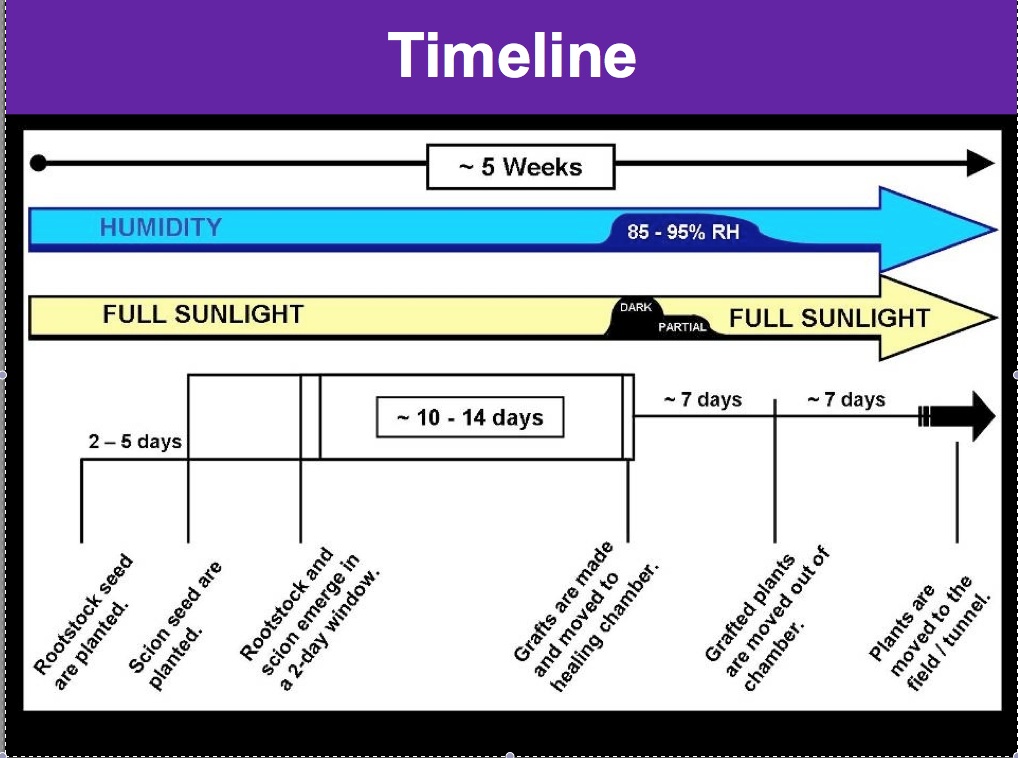

There are two methods used for tomatoes: side grafting and Japanese top grafting, also called tube grafting. Rivard uses the tube grafting method, which he says is most commonly used worldwide for greenhouse tomato production. The stems of both scion and rootstock are cut at a 45-degree angle, and the two are united with a silicon grafting clip. Grafting adds about a week to production time.

You can find many resources online to show you exactly how to do it. At www.growingformarket.com, you can search for the term “grafting tomatoes” to read the 2008 articles. Rivard has a publication at http://www4.ncsu.edu/~clrivard/TubeGraftingTechnique.pdf. His presentation is available at http://www.extension.org/organic_production under Archived Webinars. Johnny’s Selected Seeds has a video demonstration of side grafting at www.johnnyseeds.com.

Grafting tomatoes take about a week longer in the greenhouse than regular tomatoes. Rivard recommends a week in a “healing chamber” where conditions are maintained at 80-95% relative humidity and a constant 70-80°F.

Above, three examples of healing chambers where newly grafted plants are allowed to rest out of sunlight for a week. In the bottom photo, notice the cool-water vaporizer with pvc connector to direct the water into the chamber. That’s a $40 household appliance. Rivard cautions against using a warm-water vaporizer or misters.

Why graft?

The main reason to graft tomatoes is to avoid soilborne diseases. The rootstock should have resistance to the common diseases on your farm that would normally shorten the life of tomato plants or reduce their vigor and yield Soilborne diseases tend to become a problem in hoophouses when tomatoes or other Solanaceae crops are grown year after year. Most greenhouse tomatoes are now grafted.

Even if soilborne diseases are not usually a problem, grafting may produce enough of a yield increase to warrant the extra work. That’s especially true for heirlooms, many of which have very low yields.

Economics

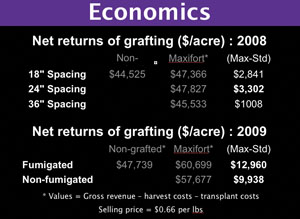

At Cedar Meadow Farm in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Steve Groff trialed grafted tomatoes against non-grafted, fumigated tomatoes. Non-fumigated, grafted tomatoes produced about 68 tons per acre, compared with less than 40 tons per acre for non-fumigated, non-grafted plants. In North Carolina, yields were as much as 53% higher for grafted tomatoes grown in a high tunnel and 42% higher. for field-grown tomatoes.

At Johnny’s Selected Seeds research farm in Maine, results have been similar. Product technician Andrew Mefferd said he trialed 17 varieties of tomatoes in a 30 x 96 foot unheated hoophouse last summer, growing both grafted and ungrafted plants of each variety. In every case, the grafted tomatoes had higher yields. Overall, for the entire hoophouse, grafted yields averaged 148% of ungrafted.

In the North Carolina trials, the added cost of propagation for grafted plants was 46 cents per plant. In Pennsylvania, where labor and heating costs were higher, the added cost was 74 cents per plant.

The biggest additional cost of grafting was for the rootstock seed. Seeds are expensive, “Plus, keep in mind that we’re overseeding by 20% to account for germination rate as well as 90% grafting success,” Rivard said.

Mefferd is convinced that the 50% greater yields being seen in grafted tomato production make it well worth the cost.

“What’s harder, grafting tomato plants or tilling up 50% more ground?” Mefferd said.

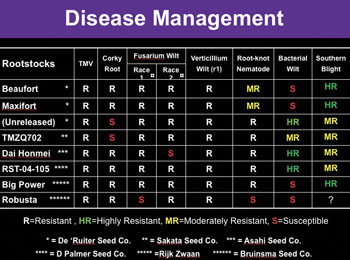

Choose a rootstock variety that is resistant to the diseases found on your

farm.

The chart on the right shows disease resistance for the rootstocks Cary Rivard used at the time of his research, and notall are available commercially. The top two on the list, Beaufort and Maxifort, are the most widely used and are available from Johnny’s Selected Seeds. Johnny’s has a new rootstock, Emperador, which has a disease package similar to Beaufort and Maxifort and is offered as an option for growers who don’t want to buy from De Ruiter, which is owned by Monsanto.

“With Geronimo, for example, you are not quite getting 20 pounds per plant ungrafted, and with grafted you are getting almost 30 pounds per plant(!) Let’s say you spend 50 cents on the rootstock seed (if you buy 250 it’s closer to 28 cents a seed), and that you are getting $2 a pound for your tomatoes. Even at that low price, you are $19.50 ahead per plant than with the plant on its own roots.”

Rivard also found better net income for grafted tomatoes sold at 66 cents a pound. The difference was not huge the first year but it was significant the second year.

All photos and tables in this article are by Cary Rivard

Insect pollination is essential to many vegetable and fruit crops, including tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, watermelons, blueberries, blackberries, apples, almonds, and many others. In the case of watermelons, there will be no fruit without pollination. Some vegetables don't require pollination to set fruit, but pollination by bees will result in larger and more abundant fruits. Nearly 75% of the flowering plants on Earth rely on pollinators to set seed or fruit, as well as one-third of our food crops, and most pollination is performed by honey bees, native bees, and other insects.

Insect pollination is essential to many vegetable and fruit crops, including tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, watermelons, blueberries, blackberries, apples, almonds, and many others. In the case of watermelons, there will be no fruit without pollination. Some vegetables don't require pollination to set fruit, but pollination by bees will result in larger and more abundant fruits. Nearly 75% of the flowering plants on Earth rely on pollinators to set seed or fruit, as well as one-third of our food crops, and most pollination is performed by honey bees, native bees, and other insects.