This article was originally published in the August 2021 issue of Growing For Market magazine.

Excerpt from The Living Soil Handbook

The following excerpt is from Jesse Frost’s new book The Living Soil Handbook: The No-Till Grower’s Guide to Ecological Market Gardening (Chelsea Green Publishing, July 2021) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Filling unused space

Interplanting excels as a way to maximize growing space in the market garden. An example of this is growing a round of radishes or lettuce below young tomatoes. Tomatoes require a couple of months to fully occupy a bed. While they grow, an interplanted crop not only provides diversity and as much photosynthesis as possible to a bed, but it contributes a financial boost for an operation. Oxton Organics, who has been growing organically since 1986 and are one of the longest running organic farms in England, grow agretti below their tomatoes. We’ve found that beets and green onions also flourish in that spot.

Other examples of maximizing bed space include green onions beside peppers, beets beside eggplant, lettuce below sweet corn. The latter example demonstrates the idea of boosting the value of slow-growing, less profitable crops like sweet corn, okra, peanuts, or edamame. If you can fit one or two hundred head lettuce plants below those plantings, it perhaps makes those crops more financially reasonable on small acreage. This is discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Filling in gaps

One of the most practical interplanting recommendations I’ve received comes from Jared Smith of Jared’s Real Food. Jared plants lettuce heads into gaps in a carrot bed when the carrot germination is poor, as shown in figure 8.5. To explain, carrots can be slow to germinate, so it may be several weeks before you realize that your carrot germination wasn’t adequate. At that point, you have to choose between continuing to tend a mediocre stand of carrots or culling it and starting over. Neither is ideal financially. Having an extra tray of lettuce to fill in the gaps makes that decision for you, because the lettuce will help bring in some revenue that is otherwise lost due to poorly germinated carrots.

Lettuces grow happily in the gaps between carrot tops in a stand of fall carrots where germination was inconsistent.

Lettuces grow happily in the gaps between carrot tops in a stand of fall carrots where germination was inconsistent.

We have also found this strategy to be so handy that we always keep an extra tray of head lettuce growing just to fill in gaps as they appear in plantings of green onions, beets, or turnips. This strategy requires the grower to relinquish their inclination to maintain a tidy aesthetic. But having a full canopy increases both the plant coverage and weed suppression while maximizing the earning potential of a poorly germinated bed. Note that most head lettuces need at least seven inches (18 cm) of space on either side of their center to head up well without disease issues. Many romaine varieties prefer closer to 10 inches (25 cm) or more. That is to say, if you do want to fill in gaps, make sure each gap is ample enough to accommodate the filler plant at maturity.

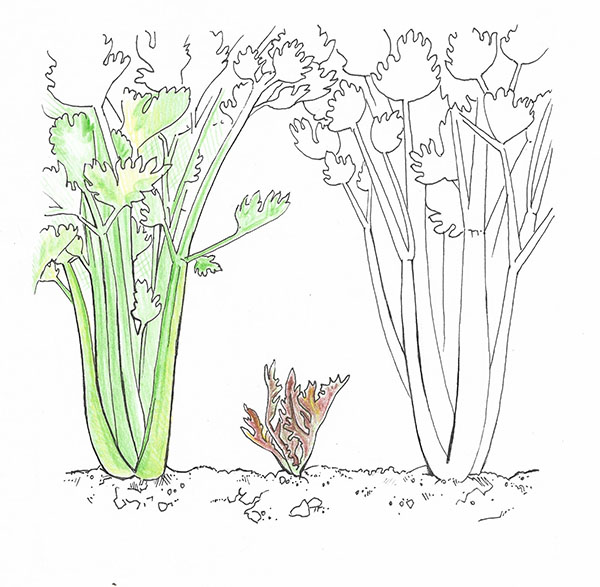

Lettuce transplanted below celery in the summer enjoys the bit of shade from the celery canopy as it establishes.

Lettuce transplanted below celery in the summer enjoys the bit of shade from the celery canopy as it establishes.

Structural benefits

Some crops have physical attributes that can offer benefits to other crops. An example of this is tall crops that can provide shade to shorter ones during the summer. We have had success transplanting summer lettuce into a celery bed a few weeks before the celery reached harvest readiness, as in figure 8.6. Lettuce is sensitive to excessive sunlight in the summer, so this little bit of shade allows the lettuce to establish in the heat with some shade before the canopy is opened up. Okra, corn, sunflowers, tomatoes, and pole beans—almost any tall crop can provide this shading effect where space allows. We’ve also observed that dense plantings of head lettuce can provide a blanching effect to green onions transplanted between the heads, which adds more of the white that customers often seek out.

The most well-known example of crops physically benefiting others is in the ancient practice of planting corn, squash, and climbing beans together (sometimes adding or substituting other crops such as sunflowers for corn). This combination, known as the Three Sisters, was originated by Mayans and other indigenous people of Mesoamerica. Today, gardeners from all over the planet utilize the Three Sisters system because it is such a productive growing method. Three Sisters is demonstrative of the structural potential of interplanting. The large corn stalks provide a trellis for the beans, and the squash provides a canopy to shade out weeds and retain moisture for the other two. (The beans don’t give much structurally to the combination, but because they sequester their own nitrogen, they don’t take much, either.)

Most natural ecosystems offer abundant examples of diversity and structural mutualism that we can easily replicate in the market garden. Corn, sunflowers, okra, or other tall crops act like trees; shorter crops like beets or lettuce act as the understory. Beans or peas are the vines, and the layered canopy of leaves effectively works to absorb all the available sun-light, preventing excessive heat from burning up the carbon and moisture in the soil. Instead, that sunlight is used to create an energy source than can be channeled underground to fuel the soil life.

Encouraging beneficials

The greater the genetic difference between plants, the greater the composition of their root exudates differs. For example, most annual flowers are of different genera than annual vegetable crops and thus contribute their own novel exudates to the soil. However, a flower’s benefits go beyond what they offer the soil. They also attract predatory bugs, parasitic wasps, flies, pollinators, birds, and other beneficials.

We plant entire beds of mixed sunflowers and other annuals, as well as inter-planting them in beds with vegetable crops. The flowers are good for beneficial insects and birds, and they can yield beautiful bouquets to sell at market, too.

We plant entire beds of mixed sunflowers and other annuals, as well as inter-planting them in beds with vegetable crops. The flowers are good for beneficial insects and birds, and they can yield beautiful bouquets to sell at market, too.

Per recommendations from Daniel Mays of Frith Farm, we tried growing sweet alyssum below nightshades (see figure 8.8) and found that they made for an excellent long-season understory. Dr. Christine Jones has recommended flax and nigella for inter-planting and insect attraction. No-dig champion Charles Dowding plants marigolds below his cucumbers to help repel aphids.

Planting lettuce to fill the space below tomato plants early in the season maximizes the production potential of the growing area as the vines mature.

Planting lettuce to fill the space below tomato plants early in the season maximizes the production potential of the growing area as the vines mature.

On our farm we have allowed cilantro, lettuce, and basil plants to bolt in and around tomato plantings because their flowers attract parasitoids so effectively. Herbs like dill can provide not only shade but bring in many pollinators as they begin to flower. Perennial herbs such as lavender, rosemary, and thyme are also abuzz with life when flowering and are excellent crops to include around your production beds where conditions allow.

Fresh-cut flowers are highly profitable per square foot, so their benefits are not limited to biology if you develop a market for selling them. A thin stand of flowers such as dill, zinnias, cilantro, and/or cosmos transplanted into gaps of lettuce or squash is one of my favorite ways to provide a little extra shade, income, and beneficials all at the same time. Try for one transplant every 10 inches (25 cm), give or take.

Dill, cilantro, buckwheat, sweet alyssum, chamomile, fennel, parsley, lavender, rosemary, thyme, daisy-family plants, and many other flowering plants attract parasitoid wasps and flies that lay their eggs in hornworms and cabbage worms and feed upon aphids. Buckwheat flowers have even been shown to increase the longevity and fecundity of certain caterpillar parasitoids.

Some parasitoids kill herbivorous caterpillars by laying their eggs inside of them, and the offspring then feed on the caterpillars as they grow. But amazingly, the parasitoid offspring feeding on the caterpillar can affect the composition of the caterpillar’s saliva, which can in turn alter the plant’s genes. For example, the saliva of the parasitized caterpillar can “tell” certain brassica plants to undergo metabolic changes that make the plant a less attractive host for future cabbage moths. Indeed, the saliva of some parasitized caterpillars has the effect of making the cabbage plant tell moths to stay away! Of course, not every interaction between these species will yield the same result, but these phenomena are fascinating nonetheless.

Maximizing profit

In order for growers to be successful using these more ecological practices, each pairing must be financially viable. Luckily, interplanting adds an abundance of value to a bed. Take peppers for instance. In the spring we plant peppers in the field around May 10. We start harvesting the first fruits by mid-July. That means there is a period of 60 to 70 days when those beds are producing no income. However, add two hundred heads of lettuce that will sell at three dollars each to the bed and suddenly that bed will be generating $600 before we harvest a single pepper. It is important to run some trials, do the math, and evaluate your results realistically, but I think you will soon discover that interplanting does not have to be solely about soil diversity. It can just as significantly be about making a living, too.

Research has suggested reductions in weeds and more efficient nutrient cycling in polycultures—both of which help a market garden financially in the long run by increasing yields and improving soil performance. But on a more practical level, growing two crops together in one bed helps decrease your susceptibility to financial loss. Take the pepper and lettuce example: If a surprise hail storm destroys the pepper plants but the peppers protect the lettuce beneath, then the bed will not be a total financial loss.

Conversely, interplanting incentivizes growing less-profitable (but no less tasty) crops like okra or sweet corn. Beds of these types of long-season, low-profit crops can be sown with radishes, interplanted with lettuce or beets, or filled in with cut flowers, adding hundreds of dollars to what are generally unprofitable, slow-to-mature crops.

Sweet alyssum planted beneath tomatoes and around other crops brings in beneficial insects such as the braconid wasp that lays its eggs in hornworms. The wasp larvae feed inside the hornworm, killing it, then emerge and spin cocoons in which they pupate, emerging as adult wasps.

Sweet alyssum planted beneath tomatoes and around other crops brings in beneficial insects such as the braconid wasp that lays its eggs in hornworms. The wasp larvae feed inside the hornworm, killing it, then emerge and spin cocoons in which they pupate, emerging as adult wasps.

The body of evidence supporting intercropping as a means for pest or disease control is increasing, and it’s a practice that can lead to higher profits for the no-till farmer. Several meta-analyses have shown that plant diversification in growing areas can decrease pest populations. The one caveat is that the measured yields in most trials were often lower in the intercropping schemes as compared to monocultures of the same crops. That said, there are also plenty of intercropping trials that have shown yield increases.

Three examples of interplanting. At left, peppers are flanked by lettuce and beets. At center, beans with small red romaine. At right, Salanova lettuce with green onions.

Three examples of interplanting. At left, peppers are flanked by lettuce and beets. At center, beans with small red romaine. At right, Salanova lettuce with green onions.

For the best yields, choose interplanting combinations that make sense for the season and the space. And remember that soil health is always a more significant influence on the outcome than the crop combination. As the title of a famous book tells us, carrots love tomatoes—but that love won’t bear fruit in compacted soil. On the other hand, fennel is notoriously antagonistic as a companion plant, but even so we have had success interplanting fennel with lettuce and celery in beds where the soil was loose and lively. A healthy, living soil always sustains crops better than a depleted or compacted soil. The most important companionship is not necessarily between the plants—though they may indeed benefit from one another—but between the plants, the sun, and the soil life.

No bed in this fall planting is planted to a single crop; instead the beds are split between two crops to increase the plant diversity.

No bed in this fall planting is planted to a single crop; instead the beds are split between two crops to increase the plant diversity.

Proven beginner combinations

Tomatoes and peppers are good crops for interplanting experiments because they can handle some competition and their growing habit leaves ample open space for several weeks as other crops slowly mature. In the spring, plant a single row of these taller nightshades down the middle of a bed with a row of head lettuce alongside, 12 inches (30 cm) from the row of nightshades, with heads spaced 8 inches (20 cm) apart. Beets can fill that same role, 4 inches (10 cm) apart in the row. A thick band of radishes is also an option. Or, start some green onion seeds in cell trays, five seeds per cell, and transplant the cells four to six inches (10 to 15 cm) apart in rows on either side, as well. Trellised cucumbers can generally take the place of the nightshades in this scenario, though keep in mind they tend to fill up space much more quickly than nightshades. They are a bit more sensitive to competition, too, in our experience.

Another easy way to ease into interplanting is just to split beds. Say you plan to plant one bed of spinach and one bed of green onions. Instead of planting a monocropped bed of each, combine them, making each bed half spinach and half green onions. The spinach, in this example, will benefit from the onions’ ability to make mycorrhizal associations and the two crops will be ready to harvest at relatively the same time. This split bed idea is perfect for our intercropping workhorses: spinach, arugula, beets, green onions, and lettuce.

Jesse Frost, aka Farmer Jesse, is a certified organic market gardener, freelance journalist, and the host of The No-Till Market Garden Podcast. He is also a cofounder of notillgrowers.com, where he helps collect the best and latest no-till insights from growers in the United States, Canada, the UK, and Europe. He and his wife, Hannah Crabtree, practice no-till farming at Rough Draft Farmstead in central Kentucky.

The Living Soil Handbook is available from Growing for Market for $29.96, or $23.96 for subscribers, who always get 20% off all the books we sell. Don’t forget to log into the website to see the discounted prices!