The benefits and challenges of sharing opportunities

My husband Casey and I started Oakhill Organics farm in 2006 on one acre of rented farmland outside McMinnville, Oregon. After working for two years on another farm, we placed a classified ad in the local paper looking for land to rent to see if an opportunity might arise. We ended up signing a lease for a great situation and were able to launch our market farm and CSA program sooner than expected. Because we’d saved money to start our farm, that first year felt full of wonderful freedoms to experiment and build our business without the burden of a mortgage or debt.

Later that summer we bought a larger piece of land that became our permanent farm home, and renting land continued to be a part of our life. Over the years, we have leased portions of our land to other farmers.

For us, the choice to share our land-base with others has been a way to add an extra income stream to our diversified farm income, and a way to pass on the blessing we’d been offered early in our farming career. Over the last 15 years, we’ve rented a portion of our land to seven different farm businesses. Most only stayed a year or two before the renter either found a more long-term solution or decided to move on from farming. Overall, our experiences have been very positive.

That being said, if you have extra land to share with other growers, there are many factors to consider before signing a lease. There are potential challenges when two or more farming operations share the same parcel. Just having enough acreage isn’t sufficient, especially if you are looking to rent to another market gardener or other grower engaged in small-scale, but high-intensity farming.

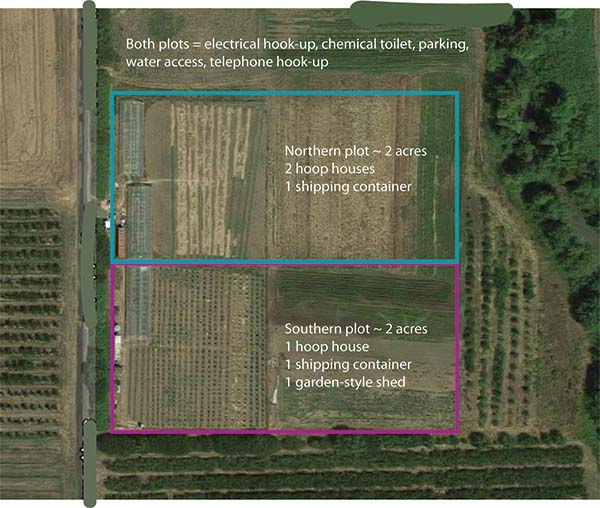

In the year that the author’s farm posted an ad online looking for new renters, they found it useful to include a map-like image to help prospective renters better understand what they had to offer. This image accompanied more generic photos of the land as well as extensive detailed text explaining the lease terms and what was included (or not). Always include as much information as possible when posting an ad or communicating with potential farmer renters.

In the year that the author’s farm posted an ad online looking for new renters, they found it useful to include a map-like image to help prospective renters better understand what they had to offer. This image accompanied more generic photos of the land as well as extensive detailed text explaining the lease terms and what was included (or not). Always include as much information as possible when posting an ad or communicating with potential farmer renters.

Here are the steps for looking for a potential renter, signing a lease, and keeping the relationship positive. While I’m directing this article at farmers with extra land to rent, the same tips apply if you are on the other side of the equation as a potential renter (as we’ve been).

What are you willing to share?

Before even considering renting land to another farmer, it’s essential to assess what you really have to share. How many acres are you willing to carve out from your own fields? How farmable is that land? Do you have enough water to share with another grower? Is there basic infrastructure that renters could use (sheds, roadways, parking, greenhouses)? Are you willing to let them develop their own infrastructure on your land? How will you share electricity bills? Is your ground eligible for organic certification? Are you willing to share some equipment or do tractor work for renters? Do you have space for someone to legally park and live in an RV? (This last one is a common request and something we do not have at our farm.)

Back in 2006, when we were looking for land to rent, these questions made us rule out many lease offers. For market growers, there is quite a lot needed to grow — it’s not a matter of just having land. What made our rental situation ideally suited that first year was access to existing outbuildings and irrigation. The owners had previously operated their own small farm on the site and still had many useful tools around that were available to us.

While these situations are ideal for the new grower — with shared infrastructure (and potentially tools) — they require you to have a very positive working relationship with your renters. It can be complicated to share well water, for example, especially if there are any limits on its flow.

For a long time, these kinds of logistics kept us from sharing the main growing area of our home property. Our farm was bare land when we bought it, and our farm operation used all the infrastructure we had built. Instead, we rented out land we had purchased next to our home farm to growers who didn’t need as much infrastructure. One was an organic kale grower, followed by an organic dairy growing silage crops.

But in 2017, we decided to carve out an acre for friends looking to start a licensed recreational cannabis operation. We were already growing licensed cannabis ourselves, as I wrote about in the May 2021 issue of Growing for Market. As part of that rental agreement, we built a fence around the acre, had a separate power drop installed, and had a shipping container and a porta-potty placed on site. We also gave them permission to build other sheds and greenhouses.

We did share the well water, which required on-going communication, but overall we made sure they had independence. This worked well enough that we repeated the formula on another acre next to that one the next summer for other friends who also wanted to start a small farm.

So, take a look at your property and assess what you are comfortable sharing. Only move on to the next steps if you have enough resources to help another grower get started.

Finding renters

We first started sharing our land base because people in our community were expressing a need. The first people to share our farm with us in 2010 were former CSA members who were looking to start their own farm and didn’t have success finding quality land to rent. They started their own market/CSA farm on three acres next to our fields on land my parents had just bought. They quickly moved on to a larger land rental situation the next summer and then purchased land that they still farm.

We found the word-of-mouth, community-based method the most effective for finding people in the area committed to farming. However, after the friends renting the two fenced acres moved on, we didn’t have anyone lined up, so we put ads on Oregon Farm Link, a regional farm connection service. These kinds of services are a great way to find a large number of potential renters, and they often offer a layer of confidentiality in the early stages of communication.

Many regions have their own Farm Links. Check with your local extension agent or search sites like Farmland Information Center’s list of programs by state at tinyurl.com/rdyx8dcb. Your local extension agent might also know of people looking for land. Other places I’d recommend posting an ad: local farming publications, a bulletin board at your farm store or natural food store, and in local newspapers or Craigslist.

Basic Farm Links simply offer listings, however, these programs have expanded greatly and many offer sophisticated support including legal and technical assistance. Land for Good in New England and Grow NYC in New York, while focusing on their regions, offer useful resources on their websites for farmers and potential renters anywhere.

Many people reached out to us in response to our Oregon Farm Link ad. I initially connected with interested parties over the phone before having people who seemed like a good fit come out to look at the site. Eventually two different parties rented the land that year (one grew CBD hemp; the other grew the Indian herb Ashwagandha).

The one big downside with using this method is that the two renters lived much farther from our farm — over an hour away — than the prior renters we’d found within our community. Their attention to the farm required more effort on their part, and we ended up needing to communicate more with them about things that were happening on the farm. It was much less successful for the renters, and both of these farmers moved on after one season.

Agreeing to terms and a lease

Once you’ve found a renter, you’ll need to have discussions about the terms and write a lease for all parties to sign. Do not skip this step. Even if the renter is your best friend, do not walk into sharing your farm based on a verbal agreement. There is too much at stake for both parties. You are making yourself vulnerable by hosting them, and they will be making a significant financial and time commitment toward their new business. You both need to be protected and have very clear shared expectations.

You can find sample leases online or buy a form at many stationary and office supply stores. We have adapted our leases from such sources over the years. If you have the money to hire a lawyer, that could be helpful, but we’ve never charged enough rent that this step has seemed to make financial sense. Of course, I am not a lawyer either, so consult legal advice if you have any questions on these topics. Again, you may find legal support at a Farm Link or related organization.

At this point in the article, readers are probably asking the Big Question: “How much should I charge to rent part of my land?” I’m hesitant to offer price suggestions, because farm rental rates vary wildly around the country and even within regions — pricing also fluctuates greatly with the real estate market as whole.

On our own farm, what we have charged different renters on a per acre basis has varied substantially depending on how many acres they were renting and how much infrastructure we were offering. The highest rates we were paid were for the fenced acre plots we rented to the licensed cannabis growers; the lowest rates were for the 30-acres of field crops. But even that rental situation allowed us to charge slightly more than the going rate at the time because the ground was eligible for organic certification already and was high-value irrigated soils.

Asking other farmers in your area about pricing can be a good place to start, but ultimately you just need to find a price that works for you and your renter. Generally speaking, the price is lower for larger tracts of bare land. Here in Oregon, the going rate can range from $110 per acre per year all the way up to $300 or more per acre per year, but please take those numbers with a grain of salt and don’t skip doing research in your own region.

However, smaller plots and/or lots with extensive infrastructure or other bonuses can go for much higher and might even be broken down into monthly payments rather than a lump sum at the beginning or end of the growing season (timing for payment is also something you’ll want to determine). I have not seen any standard “going rate” for these high value situations and would encourage you to consider what it might cost a renter to obtain the same infrastructure, spread out over time. As we farmers know, the cost of putting in things like wells, buried irrigation mainline, gravel roadways, sheds, etc. can add up fast. So if you have such amenities to offer, remember that you are saving your renters big money up-front as they start their business and price accordingly (keeping in mind their likely budget).

On your end, you’ll want to make sure the rate also covers any utility costs and work you might be expected to do as part of the rental agreement, in addition to the value of the land and infrastructure. For example, we often mowed and did primary tillage for our renters so that they didn’t need to own or rent a tractor.

I recommend including a refundable security deposit. Even the best, most conscientious renters may end up leaving your farm in a condition that requires you to do work or spend money to clean it up. The security deposit can be a helpful way to encourage them to haul all their supplies off-site when finished — and if they don’t, it can help cover the cost of hauling it yourself.

In addition to the rental rate and payment schedule, you’ll want to put into writing all those details I’ve already discussed: where are the physical boundaries of the rental, what infrastructure is available, etc. Consider what other expectations you might have, too. For example, are there particular quiet hours you’d like? Do you want to limit the number of employees the renter has on site? Do you expect them to farm in compliance with organic standards? Do you expect your renter to carry liability insurance? Put all of these expectations in writing up front, and follow up on them.

Communicating when needed

Once you have a signed lease and your renter is on site farming, you’ll want to establish healthy patterns for sharing the space. Again, having clear communication up front about shared expectations is a critical start. But it’s inevitable as you go through your first growing season together that there will be some undiscussed piece of the puzzle or one of you will find yourself challenged to meet the shared expectations.

For example, a renter might bring a dog on site and let it run past the boundaries — what if this never occurred to you to discuss and you don’t want a dog in your fields? Wait until you’re past any flush of anger from feeling a boundary was crossed, then immediately contact them. Start by assuming their ignorance that it would be a problem. In other words, approach them in good faith. In our experience, communicating as soon as possible about potential issues helps resolve them quickly to everyone’s satisfaction.

Unfortunately, it’s just not possible to avoid minor conflicts in sharing a space, so taking a proactive approach toward communication will help everyone feel positive about the rental agreement. They may approach you with a concern, so be open to hearing their side of the story, and always remember that they have a lot at stake in the relationship. I have yet to meet a new farmer who didn’t feel the pinch of too much work and not enough money in the budget. They’re trying their best to start a new business.

Healthy boundaries

The flip side of healthy communication is establishing healthy boundaries. Certainly, if you have a friendly relationship with your renter, keep it up. We have always enjoyed when our rental agreement overlapped in a positive way with our social life. For example, some of our renters have had children who would play with our children in our yard while their parents worked. That was a major win-win for both sets of farmer-parents.

But in our experience, these kinds of interactions need to be planned ahead of time and engaged in with a clear sense of respect for the other party’s time and space. I would encourage you to set the precedent in that regard by making it clear where your space is and where their space is and offer each other respect in those spaces. We would never walk into a renter’s space without their permission and most often texted ahead if we wanted to talk to make sure they were available and willing. But for the most part, we left them alone while they were working and expected them to do the same for us when we were working in our section of the field.

Because we have never offered ourselves as mentors, another important boundary for us was reminding ourselves (and sometimes our renters) that we were not co-investors in their farm operation. We always wanted all our renters to succeed in every sense, but once we’d met our end of the rental agreement, they were responsible for their own success. Occasionally — and only if it was requested — we would offer farming advice and even once or twice offered hands-on tutorials for practices like effective hoeing. And we would follow through on commitments such as helping with mowing and primary tillage. But we felt that it was very important for our renters to establish their own unique farm businesses.

Of course, this is easier to do when the other farm is succeeding rather than when it is failing. We have experienced both and have had to remind ourselves that not every life path runs smoothly and that it is infinitely better for these farmers to experiment in a rental situation than after taking on a mortgage burden. We have, on occasion, also had to remind our renters that their rental payments to us were not tied to their success. We have let people out of leases early when they realized they really couldn’t make their rent payments anymore. This is also an occasion when having a security deposit helped soften the blow to our own budget.

Renting can be worth it

I’ve made it clear that sharing your land-base with another grower isn’t simple. It can require active attention and management and have potential impacts to the rest of your own ongoing farm operation. There were days when we needed to respond to a renter’s concern while we wanted to focus on planting our fall cabbages. There have been hot summer days when our abundant irrigation well was taxed because everyone’s crops needed water at once.

However, overall renting to other farmers has been very positive for our farm. We feel incredibly blessed to own 50 acres of quality farmland on two different parcels. At times we’ve actively farmed all our land ourselves, but during the seasons of life when it hasn’t made sense, renting some of our land to others has felt like the right choice.

The rent income has helped our overall farm budget, too, often allowing us to make investments in infrastructure that otherwise would have had to wait longer. And, since our farm is located 20 minutes out of town, we’ve also enjoyed the feeling of community renting has brought to our farm at times.

Above all, we have enjoyed seeing other farmers experiment and grow and are grateful to be able to offer the same opportunity that helped us start our farming career so long ago.

Katie Kulla lives and farms with her family in Yamhill County, Oregon. You can find Katie at www.OakhillOrganics.com and on Instagram: @katiekulla.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

Here's a system to track all those details

Here's a system to track all those details

Dahlias were our number one crop this year, even beating out lisianthus and ranunculus by a landslide. We have tried many different methods of growing them, and these are the solutions we’ve come up with. I’m sure there are still better ways, and if you know of any, definitely send them our way! This year we planted 7,000 dahlias and plan to plant even more next year as we increase our growing space. Let’s just start at the beginning with planting and work our way through the whole process.

Dahlias were our number one crop this year, even beating out lisianthus and ranunculus by a landslide. We have tried many different methods of growing them, and these are the solutions we’ve come up with. I’m sure there are still better ways, and if you know of any, definitely send them our way! This year we planted 7,000 dahlias and plan to plant even more next year as we increase our growing space. Let’s just start at the beginning with planting and work our way through the whole process.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.