By Jane Tanner

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2020 Growing for Market magazine

Lorna Jackson started flower farming intensely relatively later in life at Ninebark Farm on a century-old hayfield in Metchosin at the southern tip of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. Now 64, she plans to continue into her 70s. To keep going, she makes adaptations to ease the toll on her body.

Another part of the farm’s longevity plan is profitability. Value-added, naturally-dyed silks are contributing to the bottom line along with the Island Flower Growers, a co-operative on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands of British Columbia, which Jackson helped launch last year. All these experiences — including recent adaptions for retail and wholesale sales in the time of COVID — offer lessons and inspiration to other farmers.

Many of us have interesting pre-farming careers and backstories, but Jackson’s likely ranks among the more fascinating. She was a bass player and country music singer in saloons during her 20s. During her 30s and 40s, she received a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English at the University of Victoria where she then established an academic career teaching English and creative writing while crafting her own published works. Among her books are Cold-Cocked on Hockey, A Game to Play on the Tracks, and Flirt: The Interviews.

Into her 50s and 60s, she continued teaching full-time while ramping up the farm. In other words, two full-time jobs. Last year, she cut back to half-time teaching and retires from the university this summer. Mostly, she has been farming on her own but has help from her daughter, Lily, and son-in-law, Matthew, who moved to the farm from Toronto but still work their jobs remotely.

Lorna Jackson harvesting hawthorne. All photos by Erin Wallis Photography except where noted otherwise.

Jackson’s farm is named for a native stand of physocarpus (common name, ninebark) that lines the property’s creek. In 1996, she and her husband (now ex-) built a shingled cottage on the two-acre property in the old farming community that today has about 5,000 people. In the beginning, she grew dahlias and sweet peas to sell at a neighbor’s roadside stand. Then, a local floral designer wanted more of her flowers and the business grew.

Ninebark Farm sells flowers at a busy organic farmstand down the road, the Metchosin Farmers Market, and through a 10-week bouquet CSA subscription in conjunction with The Local Food Box, a partnership of Metchosin farms. At the beginning of April, the Island Flower Growers held their inaugural wholesale market. Instead of loading flowers into a historic building in Victoria, COVID forced the market online with orders delivered by the farmers. Although big weddings are cancelled for now, a local wedding designer has been building Ninebark’s silk ribbons into her quotes. Other couples and customers are cultivated via Instagram, a vital marketing tool.

“Florals and floral design are by nature all about eye appeal,” Jackson said. “The Slow Flowers movement has also been a learn-to-take-pictures movement and Instagram images not only connect us to florists and brides, it’s also a platform for growers around the world to share trends, to problem-solve growing issues, to learn techniques, and to grow the local flower sector.”

Ninebark is in mild, rainy Canadian horticultural zone 9B (USDA zone 8B). Strong winds off the Strait of Juan de Fuca are buffered somewhat by a strip of forest along a bordering rail line. A quarter acre is in pasture for Dorset sheep. Predator pressure from cougars and bears led Jackson to reduce the livestock.

The sheep produce half a dozen lambs each year; she sells most of them for meat and keeps the meat of one for herself. Jackson continues to reevaluate predators and how safely and happily she can continue with the livestock. She wants to keep them since they’ve been part of the farm’s ecosystem for a century and add to its diversity.

Jackson cutting ranunculus.

Jackson also raises heritage free-ranged chickens. The eggs are sold through The Local Food Box CSA, though she doesn’t make money on poultry. Yet, her connections with the animals are integral to her and her farm. She butchers chickens herself and does most of the lambing.

The majority of Ninebark’s flowers are grown in no-till raised beds. Wool from sheep shearing is used as the first layer of the beds rather than cardboard. She adds chicken droppings to new beds that need to be built up. She produces compost in four concrete bins, including pig manure from her ex’s pig farm down the road. Although it can sometimes tie up nitrogen due to the wood chips in the pigs’ bedding, it is low cost and nearby. In her sustainability calculations it’s a better option than the hour drive for compost materials from the peninsula.

A century-old stone cottage on the property has a walk-in cooler and serves as her design studio. Converting the hayfield into flower production meant working around large and small rocks and adding loads of soil to amend the hard clay. No-till in the raised beds helps suppress the bindweed, thistle and dock that thrive in clay and are endemic to hayfields. She has two low tunnels and about 500 square feet in wooden raised beds outside and about 250 square feet of raised beds inside a 14-by-30 foot hoop house. She germinates seeds in a plastic greenhouse.

These days, Jackson is extending her farming tenure by adapting tasks to her age and physical issues from scoliosis and hip surgery. Last year, when she invested in a compost tea brewer for worm casting and comfrey leaf tea, she also bought a battery-powered sprayer on a cart. It’s certainly easier than hauling around a backpack sprayer.

The compost tea has already paid off by reducing insect pressure and strengthening seedlings along with newly planted flowers during their first four to five weeks in the ground. Statice stems were short before the sprayings, but now are long. Most years, dahlias need soap spray and compost tea to counter aphids.

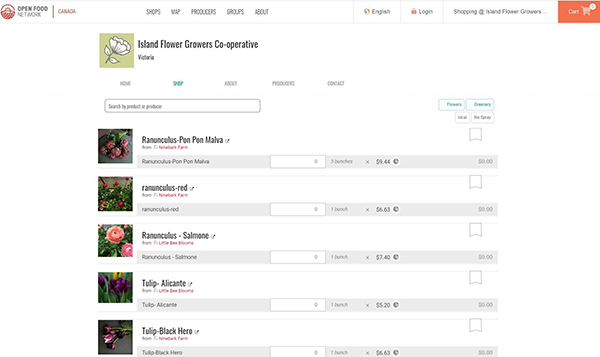

A screenshot of the Island Flower Growers Co-operative order page, which was forced online during the Covid-19 outbreak. Image courtesty of Lorna Jackson.

Avoiding injuries is a higher priority now. Jackson used to climb and descend a bank to reach the chicken coops and now walks on concrete steps she had installed. She’s conscious about wearing the right shoes and boots. She is more disciplined about rolling up netting and taking extra time to free all pathways of trip hazards.

Jackson applies lessons from the book The Lean Farm by Ben Hartman to an aging farmer. “Where to put your tools so you’re not walking far ten times a day,” she says. “It’s disheartening to look at your property and look at things that need to be put away. It’s more efficient. It’s a better way.”

Bad air was leaking in from the 100-year-old floor in the shoemaker’s cottage. So, she had it leveled and installed a concrete floor topped with foam mats for standing comfort. “These were big investments,” Jackson says. “The idea is to age in place. Farming in place is just as important to most of us. While I still had a full time job, I invested in things that would make it easier for me to stay on the farm.”

Jackson also cares for her body directly. “We’re tough and that persona of being a tough farmer, especially for women, can get in the way,” she said. “Farm work is always an imbalanced way of using your body, digging with one side, leading with the right or left hand.” She works with a pilates coach on strength and functional corrections. “If I tell her I planted hundreds of seedlings and was on my knees, she’ll address what this did to my body.”

One of Jackson’s mid-April deliveries from the Island Flower Growers Co-op. The in-person wholelsale market was moved online due to COVID and orders were organized in a school parking lot before deliveries. Photo by Lorna Jackson.

Like all farmers, Jackson gets absorbed in work and forgets to eat. To stay healthy, she always has portable food in the refrigerator. During July’s relentless farm work, she has groceries delivered. As part of self care, she sets timers to take breaks and sip tea. “I never used to do that.” For mental health, she doesn’t carry her cellphone on the farm.

Farming into the later years of life also means caring for all aspects of the land: improving the soil; ensuring rich wildlife habitats, such as making it a salmon safe property; rebuilding a border hedgerow a neighbor destroyed with herbicide.

It also means profitability and bringing discipline to all areas of the enterprise. The value-added, farm-dyed silks and increased sales through the new co-op are important revenue streams. The Island Flower Growers co-operative got funding from the provincial Ministry of Agriculture in April 2019 to hire a consultant and test business models. The collective members visited each other’s farms and sent flowers to the Vancouver flower auction, something they wouldn’t have had the volume to do individually.

At first, the auction was a positive milestone, but the sub-wholesale prices and long route, including a ferry, didn’t line up with the co-operative’s sustainability values. Last fall, they formed officially and got additional funding from Van City Bank to create a business plan, survey florists and establish a wholesale market. The groundwork helped them create a long-term, values-based infrastructure that addresses the climate crisis and helps promote profitability for the member farms.

With help from Theresa Schumilas, a flower farmer who is part of the Toronto Flower Collective, they created an online platform that tracks sales and pays a 25 percent commission to the co-operative. Jackson directs all her sales through the platform to demonstrate her commitment to the group. The co-op sells annual Buyer’s Passes, 30 as of the beginning of May. So far, money from the passes supports two co-op employees — a communications manager and a market manager — who get the word out and trouble-shoot the ordering and delivery systems among other tasks.

Ribbon dyed by Jackson with rosemary. Photo by Lorna Jackson.

The annual passes are $85 a year. People can buy a day pass for $35, for instance, for someone from out of town or with a special event. Even the co-op members purchased Buyer’s Passes, at $50 a year because many of the growers are also designers and may buy from each other. The Co-op members are asked to hold off purchasing for themselves until the last half hour of the market to give outside customers first dibs. Because the physical market has not been open during COVID, current Buyer’s Pass holders will get a full year’s access once the market is held in person.

In the midst of COVID, the inaugural and subsequent wholesale markets occurred online. The co-op already created an online pre-sale option, but during stay-at-home orders they moved all sales online. Initially, the provincial Ministry of Agriculture had allowed only food sales for markets. But the flower farmers successfully prodded officials to include flowers. One COVID uptick in sales is coming from smaller florists — studio florists — who are working from home and buying from the local flower co-op because they aren’t meeting minimums that some wholesalers require.

Overall, some of the co-op members have increased retail sales; however, others farther north didn’t have product in early spring or couldn’t make the drive because they had to scale back on employees. Ninebark’s CSA bouquet subscriptions doubled this spring and farmstand flowers were selling out.

“As with growers everywhere, we were expecting the worst and we’ve all lost weddings and events, but we’re still standing,” Jackson said. “Some days as with everyone, I’d just like to go to bed and stay there. But people are so generous expressing sincere appreciation. It is quite touching to feel we flower farmers are making a significant contribution to people’s well-being at such a painful time.”

Ribbons dyed with stinging nettle, walnut and copper beech. Photo by Lorna Jackson.

Pre-COVID, Ninebark’s silk ribbons netted more income than flowers, though it’s an arduous value-added product and increasingly competitive as others jump in. “You really need to keep strict track of your expenses and income,” Jackson said. “You can get fooled because it’s a time suck. Cutting [the silk] is hard on the body and a time-consuming process.” While she does sell torn ribbon with frayed edges, she prefers the elegant look of a bias cut which drops and flutters but requires bending over and detailed work.

Ninebark has been selling its silk ribbons for five years with most sales in Alberta and British Columbia. In an ideal world, she says she’d have more time to devote to marketing and upgrading the packaging. She has streamlined the offerings.

The plant-dyed ribbons are expensive. A ribbon just under four feet and two to three inches wide is 15 dollars Canadian. An Organza silk multi-fabric, trailing bouquet ribbon is $30. Jackson is cautious not to undercut others’ prices and doesn’t want to have her prices undercut either.

She finds the ribbon work enriching because she uses plants that have been on the property a long time. “To turn something that is beautiful into something more beautiful feels old and connected to the earth and to this land,” she said. “A bride can have a bouquet with a gorgeous bit of silk dyed with the same flowers and plants.” For instance, a bouquet with burgundy dahlias may have ribbon dyed with the same flowers resulting in a gray-green color.

There’s no set color palate because batches are never quite the same. Climate, weather, soil, watering and time of season all influence the color. Horsetail, Equisetum arvense, absorbs minerals and metals from soil, so depending on where and when she harvests, the color varies slightly. “So it’s best not to assume supplies will be replenished if you’re counting on it for an event,” she said.

Jackson employs a completely natural method, using an aluminum pot instead of adding alum as a mordant to make the silk more colorfast. She may add small amounts of iron to “sadden” or darken a color after dyeing. “As in life, saddening often results in a deeper beauty,” she says. Many of the plants are rich in natural tannins, which helps color attach to the fabric. She doesn’t use starches, sizing or fabric softener post dyeing.

The language used for dyed fabrics can be misleading. Hand-dyed refers to a non-industrial process where people put fabric into dye baths by hand, yet the dyes themselves may not be natural or plant-based. Naturally dyed usually means purchased powdered dyes extracted from plant material or dried raw materials. Jackson uses plant-dyed because she is using farm plants cooked in small batches with silk placed by hand into the bath.

Jackson walking past the old shoemaker’s cottage which serves as a design studio and houses a walk-in cooler. Photo by Erin Wallis Photography.

She has tried every plant on her farm. The following are her tried and true and the colors most requested for weddings.

The silica content of common or field horsetail means the plants must simmer in the dye pot for half a day to break the plant down and release the color. The silks placed in the dye bath come out a pale peach and gold. Bay leaves make her house smell lovely and also take a long time to release the color and result in mustard, yellowish gold silks.

During fall, she uses dried leaves that fell from a Copper Beech tree, Fagus sylvatica. They produce a rich copper color depending on how much plant material she puts in the pot. If she’s trimming limbs from a cherry tree, she’ll use the bark for dye that creates a deep gold.

The black berries of Sweet Box, Sarcococca spp., a dense, low-growing broadleaf evergreen shrub, gives her a lovely clear blue that is fairly colorfast. If she adds a pinch of iron, she gets a blue gray. Meanwhile, other plant fruit dyes aren’t colorfast. She can only use wild strawberries if it’s a week before the wedding because the blush, pale pink fades even before the silk is washed.

In late June, she shares with the robins the purple-black fruit of Indian Plum, Oemleria cerasiformis. The silks turn a purple blue. The birds don’t seem to like the fruit of Oregon Grape, Mahonia aquifolium, so she doesn’t feel as guilty taking those berries, which result in a real purple ribbon.

Rhubarb leaves create an ivory color. “You have to watch to make sure it doesn’t go yellow,” she said. Similarly, she is careful when heating burgundy dahlias because too much heat destroys the color molecule and results in an unpleasant green, instead of an incredible gray green.

Jackson scouts the farm for plant material for dyes. When she noticed a flush of mushrooms on an old pile of wood chips, she harvested a pot full which produced a pale white. “It was so beautiful, it sold out immediately.”

While playing with new plants is enchanting, Jackson is opposed to foraging and sticks to what’s on her property. “Foraging is not a benign activity,” she said. “It’s setting a precedent for others to come along and do that. It goes beyond animals and insects that would be deprived of the plants.”

She would love to dye with the beautiful blue camas that grows along the road just down the hill, but she lives on territory where indigenous communities grew Camassia quamash. “There’s a spiritual dissonance for me if I try to profit from something that isn’t mine,” she said on The Sustainable Flower Podcast from November 29, 2019, where she discussed in depth her opposition to foraging. Jackson is a deeply values-driven farmer and plans to demonstrate how farmers can continue that into their 70s.

Jane Tanner grew cut flowers and specialty crops at Windcrest Farm and Commonwealth Farms in North Carolina, and helped manage the biodynamic gardens at Spikenard Farm in Virginia.

Most flower farms evolve and change in their early years — adopting crops, markets and niches and shedding crops, markets and niches based on viability, preferences and motivation. Danielle Schami of Les fleurs Franktown House Flowers in Wakefield, Quebec, has navigated various paths during her seven years farming. Today, her focus is strengthening her region’s local flower movement and building partnerships.

Most flower farms evolve and change in their early years — adopting crops, markets and niches and shedding crops, markets and niches based on viability, preferences and motivation. Danielle Schami of Les fleurs Franktown House Flowers in Wakefield, Quebec, has navigated various paths during her seven years farming. Today, her focus is strengthening her region’s local flower movement and building partnerships.

Sarah Nixon compulsively grew flowers in her Toronto backyard and filled her house with blooms. Then, she moved on to her neighbors’ yards. Thus was born My Luscious Backyard, her floral business, an urban flower farm created with a network of back and front yards. Today, her neighbors in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood are accustomed to seeing her station wagon loaded with buckets of flowers that find their way to florists, subscription clients and weddings.

Sarah Nixon compulsively grew flowers in her Toronto backyard and filled her house with blooms. Then, she moved on to her neighbors’ yards. Thus was born My Luscious Backyard, her floral business, an urban flower farm created with a network of back and front yards. Today, her neighbors in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood are accustomed to seeing her station wagon loaded with buckets of flowers that find their way to florists, subscription clients and weddings.

Marketing is the other half of the battle

Marketing is the other half of the battle

Farming in any location is challenging. Imagine the challenge of growing crops at latitude 54.5° where winter temperatures hit minus 40° Celsius (minus 40° Fahrenheit) and a mere 100-day growing season can be abbreviated with a large dump of snow at the beginning of September. Meanwhile during the spring, Chinook winds blow and the high latitude’s strong sun alters flowers’ growing cycles.

Farming in any location is challenging. Imagine the challenge of growing crops at latitude 54.5° where winter temperatures hit minus 40° Celsius (minus 40° Fahrenheit) and a mere 100-day growing season can be abbreviated with a large dump of snow at the beginning of September. Meanwhile during the spring, Chinook winds blow and the high latitude’s strong sun alters flowers’ growing cycles.